Introduction

Shoulder instability describes a problem in which the patient has trouble keeping the ball portion ( humeral head) of the shoulder in the socket (glenoid). This can also be described as having “loose” shoulder. Shoulder dislocations are a form of shoulder instability, or one may have a shoulder subluxation in which the humeral head starts to come out of the socket but not completely.

Anatomy

Basic shoulder anatomy shows that the ball portion or humeral head is held within the socket portion or glenoid. The glenoid is fairly shallow like a plate, but is deepened by a surrounding structure called the labrum which makes it look more like a bowl. The shoulder ligaments blend into and attach to this labrum.

There are two basic way that the shoulder joint is stabilized. There are the static stabilizers which are the ligaments and labrum . Then there are the dynamic stabilizers which are the rotator cuff muscles. The rotator cuff tendon is made up of 4 muscles which blend together to form a single tendon. When the rotator cuff muscles function appropriately, they dynamically hold the ball in the socket as the arm is in use.

muscles. The rotator cuff tendon is made up of 4 muscles which blend together to form a single tendon. When the rotator cuff muscles function appropriately, they dynamically hold the ball in the socket as the arm is in use.

The shoulder ligaments are fairly complex structures because they are required to allow the hand to have a large range of motion through space, but still hold the ball in the socket. Certain shoulder ligaments are more important in different positions. Example being that the inferior glenohumeral ligament functions mostly in the abducted / externally rotated position such as the throwing position. This is a very commonly injured ligament in athletes.

When a dislocation or subluxation happens, these ligaments can be damaged. Additionally, the labrum onto which they attach can also be torn.

Causes

A shoulder dislocation or subluxation often occurs as a traumatic event. The person can point to an injury at which time the shoulder became a problem. Because the at-risk position is usually with the arm away from the body in the abducted / externally rotated position, anterior dislocations are more common the posterior dislocations.

When a shoulder dislocations, one usually has to go to the hospital to get it put back into place. Occasionally, patients do get it back into place themselves, but these are often subluxation episodes. Because the ligaments and labrum are damage dwith the traumatic event, recurrent episodes of shoulder instability and dislocation are possible. Sometimes these recurrent instability episodes happen with lesser levels of trauma, or may even be positional.

Some people are born with loose ligaments. That is, the inherent biomechanical properties their ligaments have are more “stretchy”. These people are often referred to being loose-jointed or double-jointed. There can be some advantages that these ligamentously lax people have as athletes. They make better swimmers, dancers, gymnasts, and often overhead throwing athletes. The disadvantage is that they can have problems with joint stability particularly the shoulder. It may take a much lesser level of trauma to cause a shoulder instability event in these patients. It may occur with no trauma at all, but rather due to repetitive activities. Ligamentously lax shoulder athletes will rely more on their rotator cuff to dynamically stabilize their shoulder. If the rotator cuff isn’t strong enough or not working well, they can develop instability symptoms.

Symptoms

The symptoms of a traumatic dislocation of the shoulder are usually pretty clear. The shoulder will usually lock out of place until a doctor or trainer is able to put it back in. It is often difficult for the patient to determine themselves whether it is an anterior dislocation or a posterior dislocation.

Patients who have had a traumatic dislocation episode may then develop symptoms of instability. That is, in certain positions, the shoulder feel like it is going to come out. This symptom is called apprehension. The patient will avoid these positions, usually overhead or back behind their body, to avoid this sensation of the shoulder wanting to come out. Other patients may develop pain in the shoulder if the labrum has been torn or if they have developed a loose body or other damage to the joint.

Over the age of 35, there is an increased incidence of rotator cuff tear that can occur along with the shoulder dislocation episode. This too can lead to persistent pain post-injury.

Those patients experiencing symptoms from instability associated with ligamentous laxity instead of a traumatic event may have a bigger variety of symptoms. They may have apprehension with certain activities. Pain is a common complaint as rotator cuff muscles try, but fail to control the abnormal joint motion.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of shoulder instability is usually made by talking to the patient and hearing their history of injury and symptoms. It is always helpful if an xray has been taken in traumatic episodes with

the shoulder out of place prior to it being relocated. This type of xray can confirm an anterior versus posterior event and rule out any associated fracture.

For more chronic cases, there are a variety of physical examination maneuvers that can help. These techniques are usually trying to reproduce any symptoms of positional apprehension. Also pain may be reproduced or labral tears or rotator cuff tears are present.

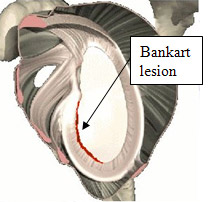

MRI scans are very helpful in traumatic cases. What we are looking for is the tearing of the ligaments and labrum away from the socket. These type of injuries are often called “Bankart lesions”. Regular MRI scan may not pick them up, so I usually request a gadolinium – enhanced MRI. In this case, the technician will injection a contrast dye into the shoulder first. The MRI will then be done with the dye in place. This dye can leak into these torn areas allowing them to be visualized.

Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed with shoulder arthroscopy. This obviously is at the time the tear is being repaired. The extent of the problem isn’t often completely determined until then. As shoulder surgeon, I have to be ready to fix everything I find.

Treatment

Conservative Treatment

Initial treatment is aimed at getting over the acute event. A sling may be given for comfort. Activities with the arm at the side are first to return. Immobilization of the arm in a sling or wrap has been shown clearly in studies not to diminish future instability. So it doesn’t matter if you hold it still or get it moving as soon as possible. Anti-inflammatories or pain medication may be used initially.

The main non-operative effort is to get the shoulder muscles working well again. There are 2 sets of muscles that control the shoulder, the rotator cuff of 4 muscles, and the 5 shoulder blade muscles. These small, controlling muscles position the shoulder bones and control the ball in the socket. If these dynamic stabilizers are not working properly, instability symptoms will be worse. There are specific exercises that need to be learned to get the strength and coordination of these muscles back. The physical therapist will teach these to you and get you over the initial injury.

This shoulder rehab program plays an even bigger role in those cases of nontraumatic, loose ligament type of instability problems. If the static stabilizers are loose, one will rely more on these muscles working properly to provide shoulder stability.

Surgical Treatment

Video of Dr. Maffet performing arthroscopic shoulder instability surgery here.

Surgery may be indicated for cases of shoulder instability that does not respond to appropriate conservative management. Arthroscopic shoulder surgery is usually possible to fix the shoulder problem. In instability cases, the surgeon must be very clear going into surgery exactly what the patient’s complaints are, and what is causing them.

Bankart labral tears are probably the most common lesion treated. Advances in arthroscopic technology allows most of the these type of labral tears to be repaired through 3 small poke holes. Labral tears that extend superiorly or posteriorly may also be encountered. It is very important that they be repaired at the same time. MRI, physical exam, and historical information help guide preoperative planning.

Surgical treatment for symptoms associated with ligamentous laxity are much less successful. It is not possible to surgically change the inherent mechanical properties of the ligament of a patient’s shoulder. If the tissue has a lot of elastin ( stretchy) fibers, surgical tightening may not work and the procedure can fail. It is very important to understand with your surgeon exact what type of shoulder instability problem you have and what the chances that surgery can help.

Rehabilitation

Even conservative treatment for shoulder instability requires a rehabilitation program. The goal of therapy will be to strengthen the rotator cuff and shoulder blade muscles to make the shoulder more stable. At first you will do exercises with the therapist. Eventually you will be put on a home program of exercise to keep the muscles strong and flexible. This should help you avoid future problems.

Rehabilitation after surgery is more complex. You may need to wear a sling to support and protect the shoulder for one to four weeks. A physical or occupational therapist will probably direct your recovery program. Depending on the surgical procedure, you will probably need to attend therapy sessions for two to four months. You should expect full recovery to take up to six months.

The first few therapy treatments will focus on controlling the pain and swelling from surgery. Ice and electrical stimulation treatments may help. Your therapist may also use massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain.

Therapy after Bankart surgery proceeds slowly. Range-of-motion exercises begin soon after surgery, but therapists are cautious about doing stretches on the front part of the capsule for the first six to eight weeks. The program gradually works into active stretching and strengthening.

Therapy goes even slower after surgeries where the front shoulder muscles have been cut. Exercises begin with passive movements. In passive exercises, your shoulder joint is moved, but your muscles stay relaxed. Your therapist gently moves your joint and gradually stretches your arm. You may be taught how to do passive exercises at home.

Active therapy starts three to four weeks after surgery. You use your own muscle power in active range-of-motion exercises. You may begin with light isometric strengthening exercises. These exercises work the muscles without straining the healing tissues.

At about six weeks you start doing more active strengthening. Exercises focus on improving the strength and control of the rotator cuff muscles and the muscles around the shoulder blade. Your therapist will help you retrain these muscles to keep the ball of the humerus in the socket. This helps your shoulder move smoothly during all your activities.

By about the tenth week, you will start more active strengthening. These exercises focus on improving strength and control of the rotator cuff muscles. Strong rotator cuff muscles help hold the ball of the humerus tightly in the glenoid to improve shoulder stability.

Overhand athletes start gradually in their sport activity about three months after surgery. They can usually return to competition within four to six months.

Some of the exercises you’ll do are designed to get your shoulder working in ways that are similar to your work tasks and sport activities. Your therapist will help you find ways to do your tasks that don’t put too much stress on your shoulder. Before your therapy sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number of ways to avoid future problems.